The Web is for Everyone

I gave this speech as the closing keynote at A11yQC, a conference on Web accessibility, on 14 October 2014 in Québec City, Canada. I have published my script here as the slides can’t really convey its message on their own.

We, as an industry, tend to have a pretty myopic view of experience. Those of us who work day-to-day in accessibility probably have a broader perspective than most, but I would argue that even we all fall short now and again when it comes to seeing the Web as others do.

I: We are surrounded by technology

We live in a bubble. We are surrounded by technology. Most of us grew up on desktops and laptops. Most of us carry at least one device on us at all times. For some of us, it’s a smartphone of some sort. For others it might be some sort of wearable—a fitness tracker or smart watch. And I’m willing to bet that a large number of us here in this auditorium may even have three or more devices on us at this very moment. I know I do.

And our technology is some of the newest, fastest, and most fully-featured in the world. Our devices are incredibly powerful and make us even more powerful, enabling us to tackle a wide range of tasks with ease. Most of the smartphones we carry come standard with pretty impressive assistive technology built in too, from adjustable text sizes to voice assist and screen reading tools to haptic, and other forms of feedback.

And they are brimming with sensors that extend our natural abilities: GPS, cameras, accelerometers. If you’re blind, your smartphone can help you pick out a matching outfit by identifying complementary colors. It can tell you who is standing in front of you by running facial recognition software. It can help you take a photograph of a document and then read it to you.

This is amazing stuff.

And, if headlines are to be believed, the smartphone revolution is spreading like wildfire. It seems nearly every other week there is some new report about how smartphone sales are continuing to soar. Heck, no one even seems to mention the humble feature phone anymore. And if you keep up with the tech press, CPUs, GPUs, operating systems and browsers keep getting faster and faster and JavaScript is the savior of us all.

The sky is the limit!

Beyond the devices we carry with us everywhere, more and more of our homes are being assimilated into the Borg of the Internet through smart appliances and fixtures like Nest. Tools like these make it easier to control our homes (and our budgets). They empower previously dependent people to live more independent lives.

And of course there’s the coolness factor of being able to turn on your heat while on your way home from work. These advancements are incredible!

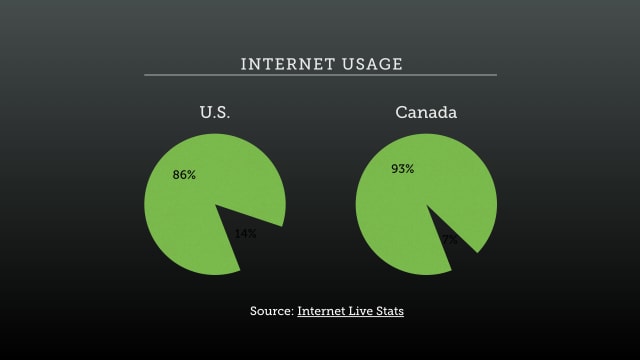

Of course, what enables all of these things to be as amazing as they are is our ubiquitous connectivity. According to Internet Live Stats, roughly 86% of Americans use the Internet. You Canadians are a wee bit more “online” at 93%.

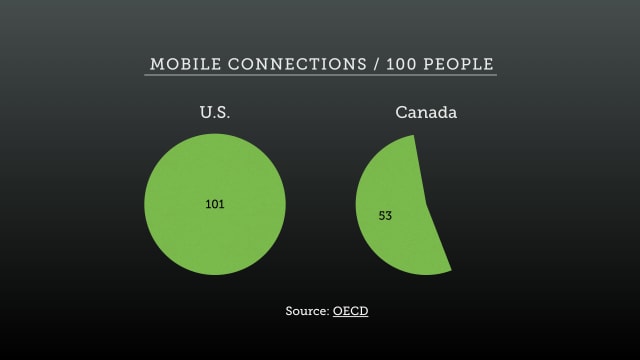

America does have you beat when it comes to mobile connectivity: there are over 100 mobile data subscriptions per 100 individuals in the U.S. (probably because of the whole multi-device thing). Mobile connections in Canada are around 53 per 100 people. (source)

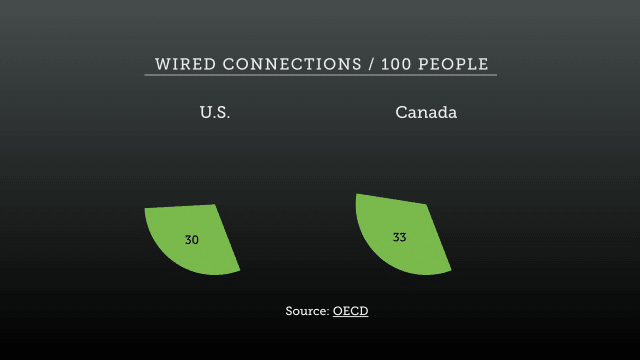

Wired connectivity is a bit lower: 30 for every 100 in the U.S. and 33 for every 100 in Canada. (source)

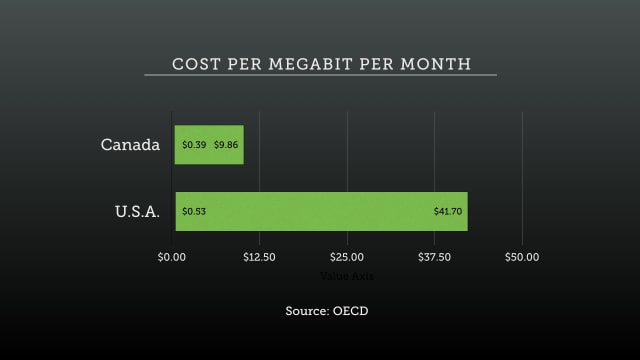

Connectivity is relatively cheap for you Canadians as well. You pay somewhere in the neighborhood of 39¢-$9.86 per megabyte per month. In the U.S., fees range widely from 53¢ to a whopping $41.70 per megabyte per month. (source)

Comcast and Rogers may be equally hated on our respective sides of the 49th parallel, but Comcast clearly sucks just a little bit more. (America!)

This technology and access makes it possible for us to live richer lives and post photos of our cats and kids on Instagram, but it has insulated us. We live in a fantasy world of speed, high definition, and Beats by Dre. Sadly, our experience is far from the reality most of the world lives in.

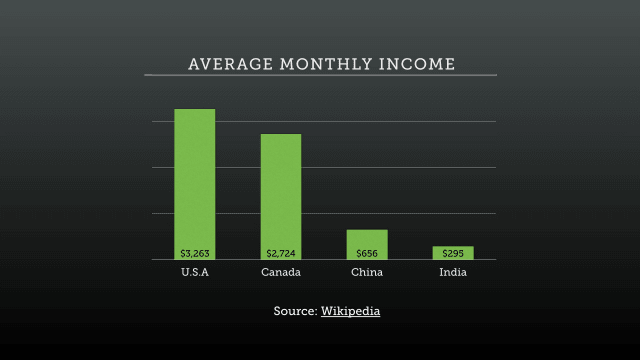

The average American takes home $3,263 a month. For the average Canadian, that figure is $2,724. By comparison, the average worker in China makes $656 a month. But that is a fortune compared to folks in India, who only take home $295 for a month of hard work. (source)

How much is an unlocked iPhone 6 again? It starts around $649. That’s more than two months salary for the average Indian. The Galaxy S5? $799 or nearly three months of hard work. In places like India, feature phones are still quite prevalent. And even when a smartphone is introduced for their market, it pales in comparison to the sort of tech we are used to seeing.

Here we have Samsung’s flagship Galaxy S5 with an amazing set of specs. A 16GB camera?! A quad-core processor?! This is the stuff of dreams for anyone who has been working with computers for more than 10 years. My first desktop was a 5150.

No not that awesome Van Halen record, this beast from IBM:

It weighted over 20 lbs, 28 lbs with two floppy drives. The screen weighed another 13 lbs and the keyboard was 6 lbs. It maxed out at 256K of memory and offered 40K of read only memory. I couldn‘t even find a spec detailing how slow the processor was, but let’s just say that the computer I began my Web career with nearly 15 years later was only a Pentium 90 with something like 16 MB of RAM.

And here, this pocket-sized computer just blows all of that out of the water.

By contrast, here we have Intex’s Cloud FX, a new phone with specs that read like the state of the art in 2007. A crappy camera, no front camera, a slow 1 GHz processor, a paltry 128 MB of RAM and barely double that in internal storage. It’s a crappy phone by our standards.

But that’s a Firefox OS phone aimed at the Indian market vs. an Android one aimed at the “developed” world. Perhaps you’d like to look at a more apples-to-apples comparison:

Here we have the BLU Dash Jr K.

Both it and the Galaxy S5 run Android 4.4 (Kitkat), but that’s where their similarities end. Look at the resolution of the Dash Jr K: 320×480 versus the 1920×1080 of the S5. Look at the processor speed. Look at the RAM.

Now, honestly, how many of you would willingly carry the Dash Jr K or the Cloud FX as your primary phone? Maybe as a laugh, maybe ironically, but I highly doubt many in our profession would subject themselves to that. Why? Because we don’t have to.

Now I don’t know your salary, but I’m willing to bet you make more money and have far more disposable income available to spend on cutting edge gadgets than most people in the world. Surely that’s the case when you compare us to China and India, but it’s equally true here in North America.

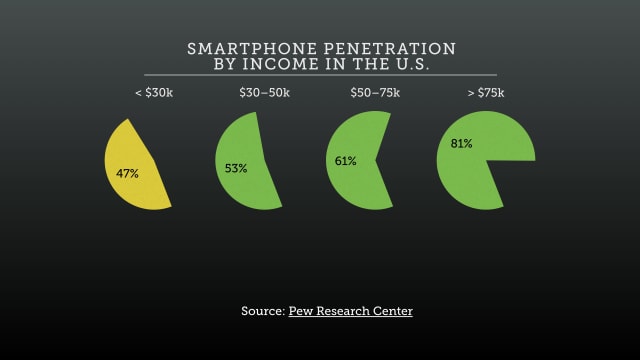

In the U.S., we see stats like “Smartphone sales accounted for nearly 85% of all mobile phone sales” and “Smartphones have reached 50% penetration” with relative frequency. But those headlines often lead us to draw incorrect conclusions about what devices people actually use to access the Web.

The dirty little secret behind that 50% penetration number is that the penetration in question was concentrated in a scant 30% of U.S. households. Kinda burying the lead if you ask me. (source)

The Pew Research Center released a study earlier this year that showed smartphone penetration in the US, broken down by income bracket. As expected, the higher the household income, the more likely you were to find someone with a smartphone.

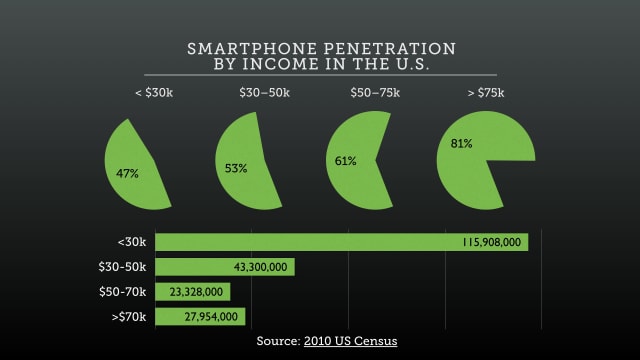

In the < $30,000 income bracket, smartphones were found in 47% of households. But it starts to get really interesting when you cross-reference that data with how many people fall into those income brackets. (source)

$30,000 was the average income in the U.S. in 2013. And, according to the 2010 census, the overwhelming majority of American households earn less than that. (source)

Now both the Samsung Galaxy S5 and the BLU Dash are technically smartphones, but one costs $43 and the other costs $799. On a limited budget, which do you think you’d be more likely to get?

Sure, in the US, carriers subsidize phone prices, but even the subsidized $199 AT&T offers the S5 for (with a 2-year agreement) ends up costing $1319 once you factor in the $40 activation and the minimum of $45 a month for a data plan.

So again I’ll ask: On a limited budget, which do you think you’d be more likely to get?

So even if a household has a smartphone, there’s probably decent odds on it being something a little lackluster compared to what we are used to carrying.

While it may not be a big deal for us to pay $60, $100, or more a month for mobile data access with fast speeds and high bandwidth limits, that would be a burden for most people. It’s worth noting that the cheaper pay-as-you-go plans typically have substantially lower data caps, frequently cost more per megabit, and often run at far slower speeds. Accordingly, while the Galaxy S5 supports blazingly fast 4G LTE speeds, both the Cloud FX and the Dash Jr K run on 2G technology.

All of this is to say that we must be hyper-aware of how big our Web pages are. Large pages with tons of high-resolution images cost our users real money and, frankly, waste their time. Some might not even load. Big Web pages are a barrier to access.

Beyond page size, we should also be concerned with how much work we we are requiring of the browser. JavaScript-intensive sites and applications can run really poorly on devices with slow processors and minimal RAM, like the BLU Dash Jr K or the Intex Cloud FX.

These are just a few of the concerns we’re having to deal with today, and only about a third of our planet is online. There are 4.8 billion people with no Internet access. But it’s coming. And when it happens, we will likely have even more to deal with. Like language barriers.

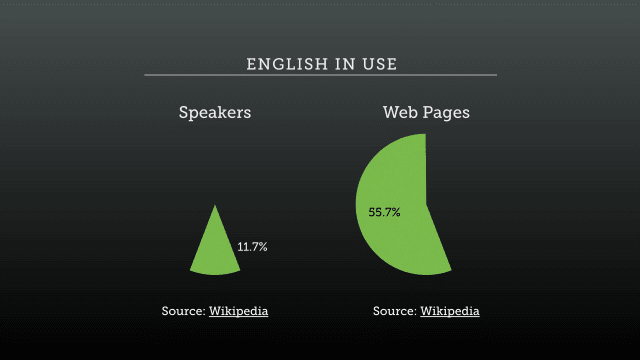

Consider this: About 11.7% of the world speaks English as its first or second language yet 55.7% of the Web is in English. (French is spoken by roughly 1.4% of the world and 4% of the Web is in French.)

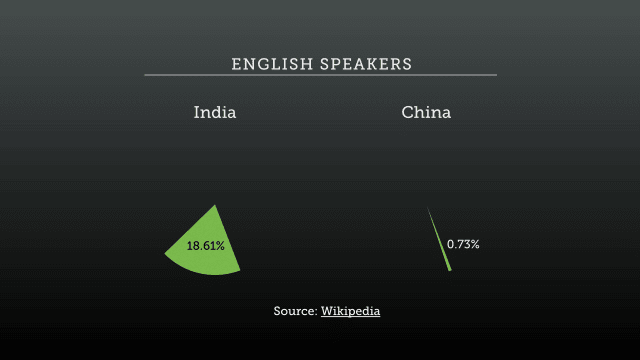

This presents some significant challenges as the Web expands into places like India and China. Only 18.61% of India’s 1.2 billion people speak English as a first, second, or even third language. In China, only about 0.73% of their 1.2 billion people speak English. Network availability is only the first of many hurdles to accessing the Web for much of the planet. (source)

We need to look beyond our technological and cultural bubble and consider how others experience the Web. As an industry, we must figure out how we can make their experiences better.

II: We are UX professionals

We are technologists who focus on accessibility, the capacity to tackle these challenges should come naturally to us. We were drawn to this field because we empathize with the struggles of others and want to help empower them to live independently.

We are user experience professionals and yet we’re often pigeon-holed outside of that practice. Our knowledge and contributions are often seen as only being applicable for people with “disabilities.” But our purview goes way beyond helping people with less than perfect vision, hearing, or mobility. Our purview is improving Web experiences for all people, regardless of physical or mental abilities, gender, race, or language.

Our purview is user experience and we need to assert ourselves and our role in that capacity.

More than most, we understand the importance of experience, of access, of independence because we work with people for whom “little things” like the ability to press a button can be a big problem. And beyond that, we also understand that experience is not a binary thing. It is a continuum.

This is a crucial fact that the Web industry is only just beginning to come to terms with. We can help ease that transition.

We are the champions of the egalitarian dream: equality of opportunity with the understanding that it does not guarantee equality of outcome or experience. We are pragmatic idealists who want to enable everyone access to amazing products and services.

We provide tremendous business value.

But we have a lot of work to do.

Sadly, many people still don’t value accessibility. They don’t get why it is important. They see it as expensive. They see it as a “nice to have”. They see it as an add-on.

I have gotten this reaction from designers. I have gotten it from developers. I have gotten it from other user experience professionals. And I have most often gotten it from managers and business owners. I’m sure you have as well.

I once had someone tell me he didn’t need to make his website accessible because he sold televisions and “blind people don’t watch TV.” I was floored. I mean holy crap!? This guy had no idea.

I had to educate him, but I needed to do it softly. I need to explain to him that his view of “special needs” was wrong. I had to be gentle because people don’t often react well to being told their world-view is fundamentally flawed. I’m sure I’m not the only one in this room who has been in a situation like this either.

If our primary job is to empower people to live independently, our second job is surely to educate the world, not just on how to make the Web more accessible, but why it matters. We need to bring everyone into the fold.

I love exercises that create opportunities for revelation. One of my favorites originates from John Rawls. Rawls was a philosopher who used to run a social experiment with students, church groups, and the like.

In the experiment, individuals were allowed to create their ideal society. It could follow any philosophy. It could be a monarchy or democracy or anarchy. It could be capitalist or socialist. The people in this experiment had free rein to control absolutely every facet of the society… but then he’d add the twist: They could not control what position they occupied in that society.

This twist is what John Harsanyi—an early game theorist—refers to as the “Veil of Ignorance” and what Rawls found, time and time again, was that individuals participating in the experiment would gravitate toward creating the most egalitarian societies.

It makes sense: what rational, self-interested human being would treat the elderly, the sick, people of a particular gender or race or creed or color, poorly if they could find themselves in that position?

We’re often put in a box and told to only concern ourselves with folks with “special needs.” Well news flash: we all have special needs. Some we’re born with. Some we develop. Some are temporary. Some have nothing to do with us personally, but are situational or purely dependent on the hardware we are using, the interaction methods we have available to us, or even the speed at which we can access the Internet or process data.

We need to look beyond the world of assistive Web technology and explain the value and insight we bring to approaches like Responsive Web Design. After all, what is RWD about if not access? Yes, its fundamental tenets are concerned with visual design, but in terms of the big picture, they’re all about providing the best possible reading experience. Responsive web design is also a perfect example of the continuum of experience we are so intimately familiar with.

We understand special needs. We understand fallbacks. And we understand how to design robust experiences that work under a wide variety of conditions. That knowledge is invaluable.

We are invaluable.

III: We are the future

This is an incredibly exciting time to be working in accessibility. User experience is becoming central to how organizations work and how they design their products and accessibility should be at the core of that.

This is our time!

The more influence we have on the products and services our companies and clients create, the more places they can go and the more successful they will be.

Take WhatsApp for instance. Fundamentally, it is a chat application. That’s not terribly groundbreaking. But it developed into a way to avoid costly SMS messages. Still, even that’s not all that special: the App Store lists over 7,900 messaging apps for the iPhone.

What made WhatsApp matter was the shrewd business decision to move beyond the bubble. They chose to embrace access and embrace diversity. They made their messaging application available on a ton of platforms, especially low cost ones. So sure, they support iOS and Android, but unlike a lot of app developers, they officially support Android 2.1+, iOS 4.3+, Blackberry 4.7+, Symbian, Nokia Series 40, Windows Phone. Some of those aren’t even smartphone OSes!

While many may not consider this an “accessibility” win, it absolutely is. WhatsApp made a decision to open up access to their messaging application to people who were traditionally ignored by mobile app developers. And they were rewarded handsomely for this: as of last count, they had somewhere around 600 million users globally. And then there’s that little thing about them selling to Facebook for $19 billion.

And WhatsApp isn’t a fluke in benefiting from making itself more accessible: China’s WeChat boasts a user base of 600 million and Japan’s LINE has over 400 million users. All of these messaging platforms have benefitted greatly from embracing devices and technologies available to people outside of our bubble.

We can and should be advising our companies and clients on why and how to be more accessible. We need to look at the big picture and we should not be afraid to be bold in asserting that accessibility creates opportunity.

We already know that strong content guidelines pay dividends by creating opportunities for our content to work harder for us. Not only do they improve the readability of content on the sites we build, but they facilitate social sharing through more engaging summaries and headlines.

The clear, well-written, jargon-free content we advocate for is easier to translate into other languages. It also makes the content easier to follow via screen readers and other vocalization tools like Readspeaker, which in turn makes it possible to offer novel ways of accessing our content, like automated podcasts.

Our focus on semantic, meaningful, markup allows our content to be pulled into other contexts including focused reading apps like Pocket, Readability, and Instapaper.

And while we can certainly do a lot to make rich, JavaScript-based interactions far more accessible to assistive technology, our advocacy for progressive enhancement ensures that our content and tools work no matter what.

Let’s say an ISP blocks jQuery as malware. No problem.

Let’s say the page is taking a long time to download on a high-latency mobile network (or hotel Wi-Fi). No big deal.

The products we build just work because we know that we don’t control how they are delivered.

It’s our job to educate others on this reality and to demonstrate why these are central to user experience.

IV: We are Agents of Change

The shift to handheld computers has been huge for accessibility. After all, the computers in our pockets are assistive technology. This is our world!

I’m going to make a somewhat bold prediction: while touch has been revolutionary in many ways toward improving digital access, voice is the future. And the user experience of voice-based interfaces is going to be critical in creating more opportunities for people to interact with and participate in the digital world.

We’ve got the jump on the other folks working in user experience when it comes to voice: We’ve been considering how interfaces sound for years. On top of that, we already understand how to design alternate interaction methods because we see experience as a continuum.

As voice UX technology—for example, Siri, Google Now, and Cortana—improves, we should be the ones people should look to as the experts. We will empower the next generation of websites and applications to become voice-enabled. And in so doing, we will improve the lives of billions. Because “accessibility” is not about disabilities, it’s about access and it’s about people.

Sure, we’ll make it easier to look up movie times and purchase tickets to see the latest Transformers debacle, but we will also empower the nearly 900 million people globally—over 60% of whom are female—that are illiterate. And that’s a population we have not traditionally viewed as our purview either.

We will create new opportunities for the poor and disadvantaged to participate in a world that has largely excluded them. You may not be aware, but 80% of Fortune 500 companies—think Target, Walmart—only accept job applications online or via computers.

We will enable people who have limited computer skills or who struggle with reading to apply for jobs with these companies.

We will empower immigrants to read lease agreements and their postal mail.

We will enable people with visual disabilities to vote, even on paper ballots, without human assistance.

We can help bridge the digital divide and the literacy gap. We can create opportunities for people to better their lives and the lives of their families. We have the power to create more equity in this world than most of us have ever dreamed.

This is an incredibly exciting time, not just for the accessibility experts, not just for user experience, not just the Web, but for the world! I can’t wait to see how awesome you make it!

Thank you.

Webmentions

Likes

Shares